The Varied Cultural Customization Needs of Santa Claus Imagery

Santa Claus looks deceptively simple from a distance: a jolly man in a red suit, white beard, sack of gifts, and a sleigh full of reindeer. In on-demand printing and dropshipping, that standardized “Coca‑Cola Santa” is on everything from hoodies to mugs. But once you start selling across borders, you discover what folklorists and historians have documented for years: Santa is not one character but a crowded family of gift‑bringers, saints, goats, witches, trolls, and angels.

As an e‑commerce mentor, I see this clash often. A store scales internationally with a single Santa visual strategy, only to learn that in Spain the big emotional day is January 6, in the Netherlands the key figure looks like a bishop in November, and in parts of Central Europe the most recognizable winter icon is a witch on a broom or a horned demon. The lesson from the historical and anthropological research is clear: Santa imagery is one of the least “one‑size‑fits‑all” assets in your holiday catalog.

This article distills that research into a practical framework for cultural customization. The goal is not academic trivia; it is to help you design Santa imagery that respects local traditions, avoids obvious pitfalls, and unlocks new product lines instead of closing doors.

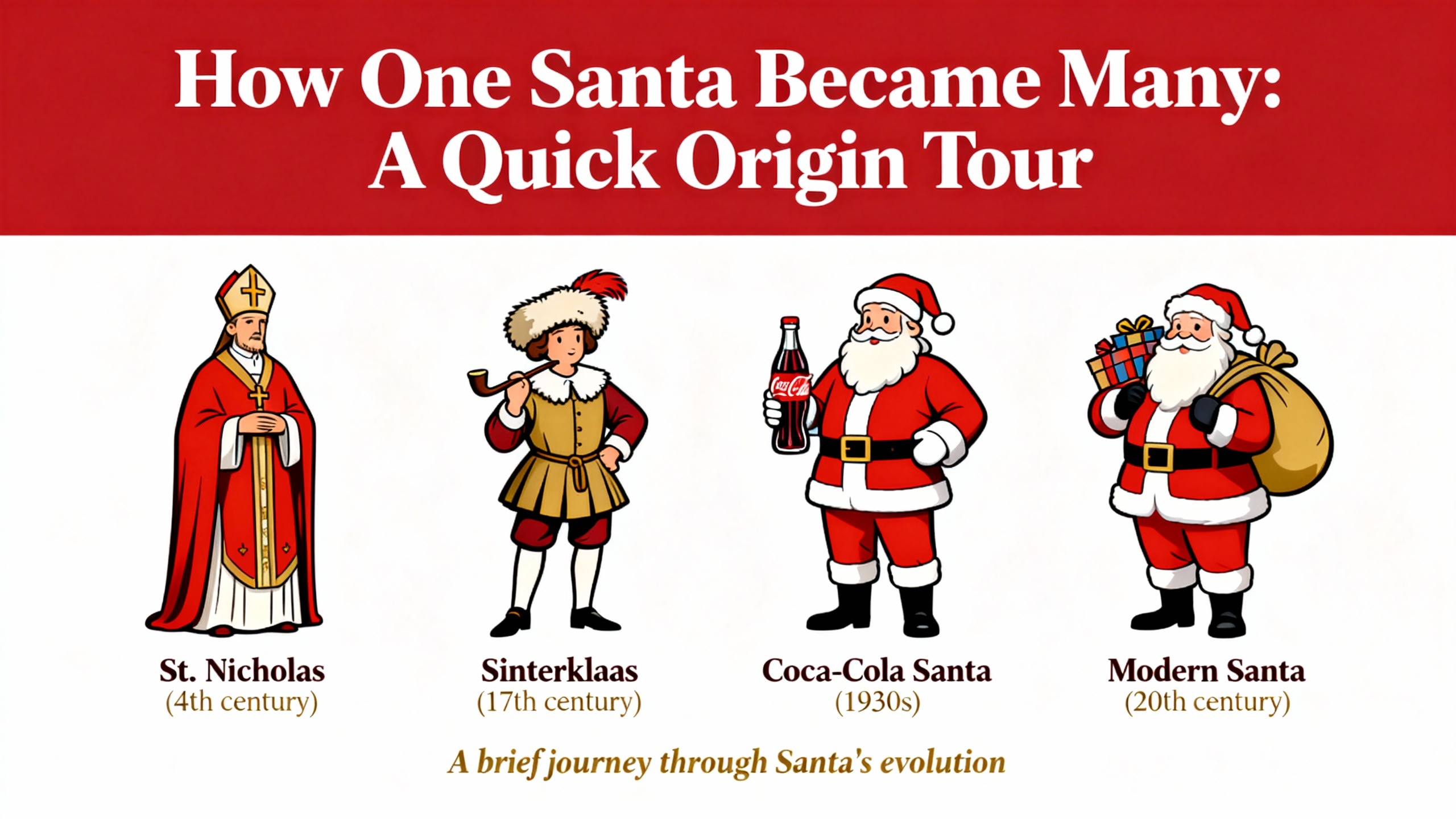

How One Santa Became Many: A Quick Origin Tour

Before you customize Santa, it helps to understand what you are actually customizing.

From Saint Nicholas to Sinterklaas and Santa

Most of the sources agree on the starting point: Saint Nicholas of Myra, a Christian bishop in the early centuries of the church, probably based in what is now Turkey. Accounts from church history and Catholic sources describe him as a figure of quiet generosity, famous for secret gifts to children and the poor, including the story of throwing bags of gold through a window to provide dowries for three sisters. His feast day, December 6, became a major children’s gift‑day across Europe, with modest presents like nuts and fruit reinforcing his role as patron of children and charity.

As Christianity spread, Nicholas was localized. In the Netherlands he became Sinterklaas, a tall bishop in red robes arriving in early December by ship from Spain, riding a white horse over the rooftops. Dutch traditions described children leaving out shoes with hay or carrots for the horse and waking to find sweets and small gifts. That shoe‑based ritual appears in several European cultures, including Hungary, Croatia, and Poland, where Mikulás or related figures fill boots rather than stockings.

Dutch settlers carried Sinterklaas to New Amsterdam, later New York. Writers like Washington Irving used him in playful histories of the city, describing him flying through the sky and visiting chimneys. Historian Stephen Nissenbaum, writing about early nineteenth‑century New York in a study of Christmas, argues that elite New Yorkers essentially invented a “Dutch” Santa to promote quieter, family‑centered Christmas customs in place of rowdy winter revelry. They claimed tradition but were, in effect, creating a new one.

Nineteenth‑Century Standardization: Poems, Pictures, And Prints

The next big leap came from literature and illustration. In 1823, the poem usually known as “’Twas the Night Before Christmas,” attributed to Clement Clarke Moore, reframed Nicholas not as a solemn bishop but as a “jolly old elf” arriving on Christmas Eve. The poem defined core features that still dominate modern Santa imagery: a fur‑trimmed suit, a round belly that shakes like jelly, a sleigh pulled by eight named reindeer, stealthy chimney entry, stockings filled with toys, and a magical finger‑on‑the‑nose gesture as he departs.

Illustrators translated that verbal image into visual form. American cartoonist Thomas Nast, publishing in Harper’s Weekly from the 1860s onward, repeatedly drew Santa, gradually enlarging him from a tiny elf into the full‑sized, jovial figure we recognize. Nast added crucial world‑building details: a North Pole headquarters, a workshop staffed by elves, lists of good and bad children, and scenes of Santa reading letters. Researchers at the Anchorage Museum and public‑domain archives emphasize how Nast’s repeated images standardized Santa’s round body, thick beard, and winter clothing decades before mass advertising.

By the late nineteenth century, Santa’s image was appearing on cards, prints, and home décor across the United States. He was not always in red; nineteenth‑century art shows him in green, brown, blue, and natural fur tones. But the combination of beard, gift sack, winter setting, and joyful demeanor anchored the archetype.

Twentieth‑Century Santa: From Harper’s To Global Icon

In the twentieth century, commercial art amplified that evolving image. Christmas historians point out that illustrator Haddon Sundblom’s work for Coca‑Cola beginning in 1931 did not invent Santa’s red suit, but it did project one particular version of him into magazines like The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, National Geographic, and The New Yorker on a massive scale. Sundblom’s Santa was warm, approachable, and consistently dressed in bright red with white trim.

By mid‑century, department‑store Santas, films such as “Miracle on 34th Street,” and television specials had reinforced this look as the default in North America. A historian at Canisius College notes that Santa, though rooted in a Mediterranean bishop, had become a distinctly American folk figure, blending Old World saint with New World expansiveness and optimism.

Yet even as this standardized Santa spread, older and alternative figures remained strong or even resurgent in other cultures. That is where cultural customization really begins.

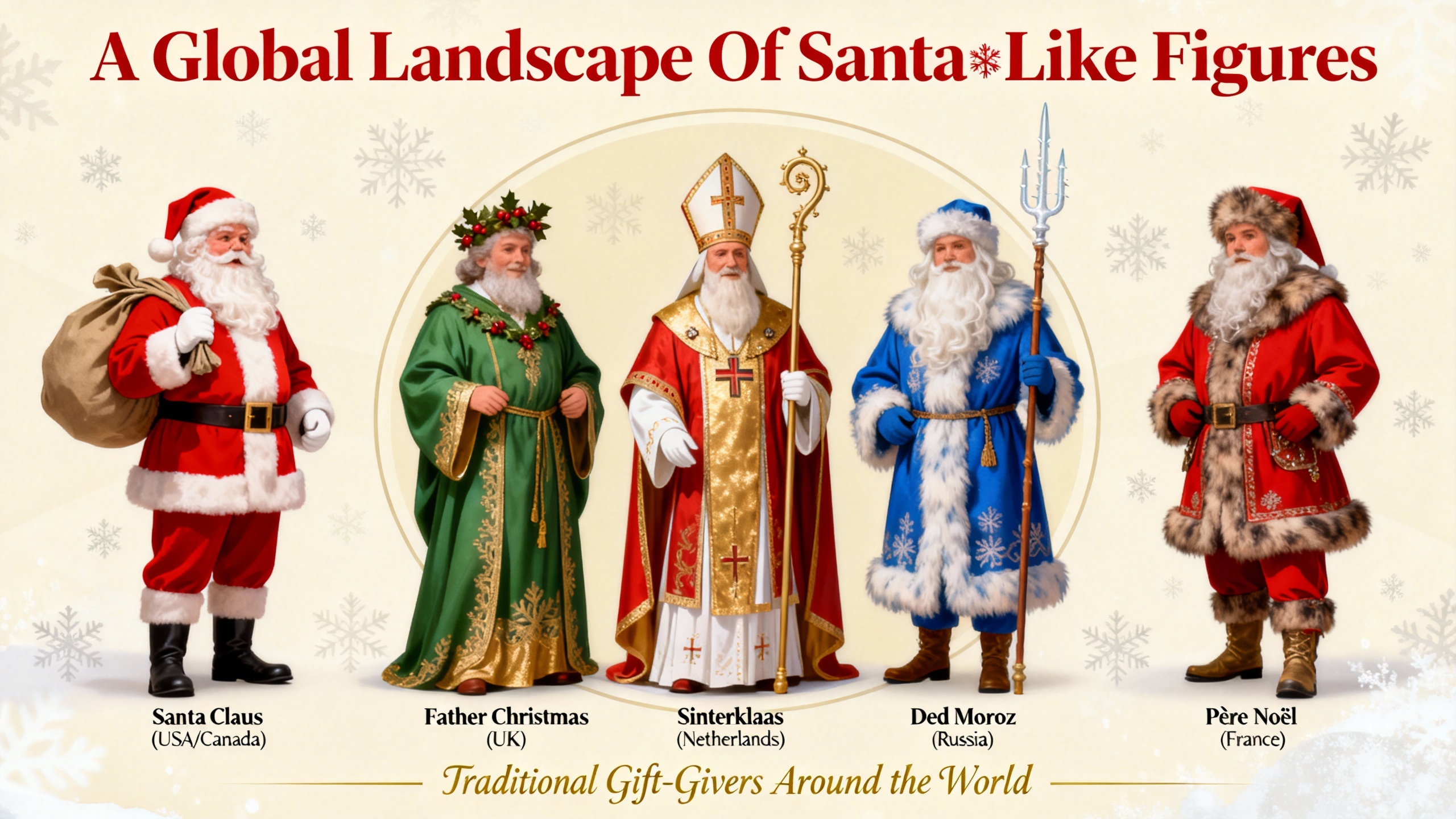

A Global Landscape Of Santa‑Like Figures

Looking across ethnographic and historical sources, a pattern emerges. Santa‑like figures vary along a few practical axes: when they arrive, what they look like, how they travel, who accompanies them, and what moral story they tell. For a print‑on‑demand brand, these axes become design levers.

Calendars: When The Gifts Come

North American e‑commerce tends to anchor everything on December 24 and 25. Globally, the gift calendar is far more complex.

In much of Europe, the older gift date is Saint Nicholas Day. Dutch and Belgian children expect Sinterklaas around the evening of December 5, with his feast on December 6. In Hungary, Croatia, Poland, and neighboring countries, Mikulás or equivalents fill shoes or boots at doors on the night leading into December 6, leaving treats for well‑behaved children and symbolic twigs or coal for misbehavior.

On the other end of the season, many cultures center Epiphany on January 6. In Spain and many Spanish‑speaking communities, the Three Kings, or Los Reyes Magos, process through cities in parades called Cabalgatas on January 5 and leave gifts in children’s shoes overnight. In Italy, the primary figure on January 6 is Befana, a kindly witch who flies by broomstick and delivers sweets or coal, tied to a legend that she searched for the Christ child after missing her chance to join the Magi. Reporting from Spain and Italy consistently stresses how emotionally significant January 6 remains, even where Santa or Papá Noel has grown in influence.

In Russia, Ukraine, and parts of Eastern Europe, New Year’s Eve is the main gift‑night. Ded Moroz, or Grandfather Frost, dressed in a long coat and boots, arrives with his granddaughter Snegurochka and distributes gifts at New Year’s parties. Sources on Russian and Soviet history note that during the Soviet period Ded Moroz took on a strong ideological role, sometimes prompting children in public events to thank Stalin for “all the good things in socialist society.”

Even beyond Christian calendars, related figures appear at other festive moments. In Iran, Amu Nowruz, sometimes called Papa Nowruz, is a bearded old man who brings gifts at the spring New Year, accompanied by Haji Firuz with tambourine and songs. In Japan, Hoteiosho, a rotund, jolly monk from Buddhist tradition, brings gifts around the New Year and is said to have eyes in the back of his head to watch children.

For a global brand, this means Santa imagery tied solely to December 25 misses opportunities. Artwork and messaging that acknowledges December 6, New Year’s, and January 6 can resonate deeply where those dates carry the real emotional weight of gift‑giving.

Clothes, Colors, And Climate

The classic red suit is just one outfit in Santa’s wardrobe.

In the Netherlands and Belgium, Sinterklaas is not a fur‑suited elf but an elderly bishop in a long red robe and tall mitre, carrying a golden staff. In England, the older Father Christmas tradition shows him in a green cloak with a wreath of holly and ivy and a staff, closer to the Ghost of Christmas Present in Dickens than to the American mall Santa. English and German sources trace that green‑cloaked figure back to pre‑Christian winter festivals, where he represented feasting and seasonal abundance.

French Père Noël typically appears in a long, fur‑lined red cloak with hood, sometimes closer to a traveling robe than a tailored suit. In parts of Germany and Central Europe, the Christkind or Christkindl is an angelic, often female figure with a crown and long blond hair, rather than an old man at all. Protestant leaders like Martin Luther deliberately promoted this Christ‑child gift‑giver as an alternative to saint veneration, a detail still visible in German‑speaking countries where both Christkind and Weihnachtsmann coexist.

Climate adds another layer. In Brazil, Papai Noel wears a lighter silk version of the red‑and‑white suit and leaves gifts under trees made of electric lights, a practical adaptation to summer heat and urban settings in the Southern Hemisphere. Australian sources describe a “Summer Santa” swapping heavy winter garments for board shorts, sunglasses, and sometimes a Hawaiian shirt, reflecting beach barbecues and outdoor celebrations at Christmas. In Hawaii, Kanakaloka may appear in a relaxed tropical outfit, arriving by canoe or surfboard.

In Russia, Ded Moroz usually wears a long blue or sometimes red coat with traditional Russian styling and tall winter boots. Finnish Joulupukki, whose name literally means “Christmas goat,” is dressed in red but inherits goat‑related symbolism from older Scandinavian solstice customs. Swedish and Norwegian tomte or nisse are small, gnome‑like figures with red caps, often in simple work clothes rather than ornate suits.

For visual designers, these differences are not cosmetic trivia. The cut of the coat, the color palette, and even the character’s body type signal which tradition you are invoking. A bishop’s mitre, a green cloak, a silk shirt, or a blue coat each tell a different story.

Transport, Animals, And Props

Santa’s sleigh and reindeer dominate American imagery, canonized by Moore’s poem and later songs. Around the world, his counterparts travel very differently.

The Dutch Sinterklaas rides a white horse, still reflected in traditions where children leave carrots and hay for the animal. Croatian and Hungarian children also leave shoes or boots to be filled. In several cultures that honor the Three Kings, children leave hay for camels instead of treats for reindeer.

Scandinavian traditions link Santa figures to goats. Finnish Joulupukki and Swedish Jultomten connect to the Yule Goat, once a fearsome spirit demanding gifts and food, now a decorative straw figure and a symbol of Christmas. In some accounts, the goat pulled the gift‑giver’s sled rather than reindeer. Norwegian and Swedish nisse or tomte are “house spirits” who sometimes travel with goats and demand porridge or glögg in return for their help.

Russian Ded Moroz rides a sleigh drawn by three powerful horses. In Hawaii and parts of Australia, localized Santa figures arrive by canoe, surfboard, or even jet ski, underscoring a seaside Christmas. In some French regions, Père Noël’s companion animals are flying donkeys rather than reindeer.

Even props vary. Stockings are not universal; many European traditions use shoes or boots by doors or fireplaces. In Catalonia, Tió de Nadal is literally a log with a painted smiling face that “defecates” gifts after children feed it and then beat it with sticks while singing comic rhymes. In Iceland, the thirteen Yule Lads leave gifts or rotten potatoes in shoes set on windowsills on the nights before Christmas.

For product design, this means the familiar reindeer sleigh is only one of many credible transport motifs. Swapping in horses, goats, camels, or surfboards where appropriate can make a design feel native rather than imported.

Companions, Dark Twins, And Moral Stories

Many Santa figures do not work alone. Their helpers and antagonists carry important cultural messages.

Dutch Sinterklaas historically travels with Zwarte Piet, a figure in colorful clothing whose blackface depiction has generated intense controversy. Reporting from Dutch and international media, along with research briefs, document how critics view the traditional costume as a racist caricature rooted in colonial imagery. Aruba, a former Dutch colony, has officially banned blackface makeup for Sinterklaas celebrations and encouraged multicolored or otherwise revised versions of Piet.

In German‑speaking regions, Saint Nicholas is often paired with darker companions. Some names recorded in German folklore include Knecht Ruprecht, Belsnickel, and characters like Hans Trapp or Klaubauf, who act as stern enforcers, handing out switches or threatening to carry misbehaving children away. In Austria and parts of Central Europe, Krampus, a horned, half‑goat, half‑demon figure with a long tongue, serves as Nicholas’s frightening counterpart. Modern festivals feature people in elaborate Krampus costumes parading through streets on Krampusnacht, often on December 5.

French Père Noël may be joined by Père Fouettard, the “whipping father,” who punishes naughty children. In Iceland, the Yule Lads are the mischievous sons of the ogress Grýla, who according to legend kidnaps and eats misbehaving children, aided by a giant Yule Cat that punishes those who fail to receive new clothes.

Anthropological work, including essays in Scientific American, interprets these figures as embodiments of what sociologist Emile Durkheim called a shared moral sensibility. They personify the idea that someone is “watching” and that generosity is linked to behavior, even though in practice most children receive gifts regardless. The now‑standard “naughty or nice” list in modern Santa lore extends that logic in gentler form.

For brand owners, these dark companions create both risk and opportunity. They are powerful, visually distinctive motifs that can anchor alternative or “edgier” Christmas collections. But they also tap into fear, discipline, and, in some cases, racial stereotypes. Careful handling is essential.

Cultural Sensitivities Embedded In Santa Imagery

The research base on Santa is unusually rich in discussions of ethics, race, and politics. Ignoring that context when you commercialize Santa can backfire.

Race, Representation, And The North

Debates around Zwarte Piet in the Netherlands and Aruba illustrate how quickly Santa imagery can become a flashpoint. Journalistic reporting and cultural analysis from Dutch and international sources describe how Black Pete costumes historically involved white performers in dark face paint, curly wigs, and exaggerated red lips, presented as “Spanish Moors” or servants. As Dutch society has become more diverse and global conversations on race intensified, this has drawn strong criticism.

Activists and commentators have urged replacing Black Pete with non‑racialized helpers or changing the visual to soot‑smudged faces that reflect chimney work rather than inherent skin color. Aruba’s culture ministry has explicitly discouraged blackface, encouraging multicolored alternatives. For a product designer, this means classic blackface Piet imagery is not merely “traditional”; it is widely seen as harmful.

At the same time, the Anchorage Museum’s work on Santa as a “Northern icon” highlights another blind spot: the default whiteness and emptiness of the North in Santa imagery. The museum’s researchers point out that the global Santa image situates him at the North Pole in a pristine, snow‑covered wilderness, often without any visible Indigenous people or local cultures. This feeds into long‑standing colonial narratives of an “empty” Arctic available for exploration and claims.

The article also notes that Santa has been used as a symbolic pawn in Arctic geopolitics. A Russian expedition famously planted a flag on the seabed at the geographic North Pole in 2007, while Canadian politicians, leaning on old “sector theory” maps, have publicly joked that “Santa is Canadian” to support territorial claims. Again, for e‑commerce this is less about the law and more about imagery. A North Pole that appears exclusively white, male, and uninhabited can unintentionally reinforce erasure.

Religion, Ideology, And Cultural Engineering

Some Santa variants carry explicit political baggage. In Ukraine, for example, sources report that Saint Nicholas was historically the children’s gift‑bringer, with presents appearing under pillows around December 19 in the Julian calendar. During the Soviet era, state authorities sidelined this Christian figure and installed Ded Moroz and the secular “New Year tree” as official holiday symbols. After independence, many Ukrainians revived Saint Nicholas and came to view Ded Moroz as a foreign, Soviet imposition. In that context, decorating your Ukrainian‑targeted products with Ded Moroz can read very differently than using him for a Russian audience.

Ded Moroz himself has a documented history as a tool of Soviet messaging. An article drawing on mid‑twentieth‑century reporting notes instances where Ded Moroz would end events by asking children to whom they owed “all the good things in socialist society,” prompting them to reply “Stalin.” This does not mean contemporary Eastern European families who enjoy Ded Moroz imagery endorse that history, but it does mean the figure is not ideologically neutral.

Protestant Europe offers another kind of cultural engineering. Martin Luther’s promotion of the Christkind, an angelic Christ‑child gift‑giver, aimed to shift focus away from saints like Nicholas and toward Jesus himself. As a result, many German‑speaking and Central European regions still juggle multiple gift‑bringers: the Christkind in some areas, the red‑suited Weihnachtsmann, and Saint Nicholas on his feast day. Catholic and local sources emphasize how these figures coexist and reflect differing religious emphases.

Scholars of Nordic folklore also warn against over‑simplifying Santa’s roots. A detailed analysis of Scandinavian tomte traditions notes that while there may be some connection to Sámi imagery and broader Nordic myth, the modern global Santa has a well‑documented American development. Claims that Santa is primarily a Sámi mushroom‑shaman figure, popular in some modern internet lore, are not well supported by historical evidence. For brands, building campaigns on such speculative origin stories risks not just inaccuracy but also appropriation of Indigenous cultures for novelty.

Designing Santa For On‑Demand Printing: A Practical Framework

Once you understand the historical and cultural landscape, the customization problem becomes a design strategy challenge. Santa imagery affects product appeal, brand trust, and social risk. Here is how to translate the research into practical e‑commerce decisions.

Decide Which Gift‑Bringer Your Customer Actually Cares About

In many markets, the red‑suit Santa is present but not central. In Spain, emotional energy is often attached to Los Reyes Magos on January 6. In Italy, Befana on Epiphany Eve remains a beloved figure, even alongside Babbo Natale. In Central Europe, parents may stage Saint Nicholas visits in early December, Christkind on Christmas Eve, and sometimes a Santa‑like figure as well.

If your catalog for a given country features only the American Santa, you are speaking to globalized imagery but ignoring local emotional anchors. A wall print of the Three Kings processing through a city and leaving gifts in shoes may resonate more deeply with Spanish families than another reindeer sleigh. A whimsical illustration of Befana on her broom, or a kind version of the Yule Lads peeking over a windowsill, may feel more “ours” to Italian or Icelandic buyers than a generic North Pole scene.

The same applies to Saint Nicholas Day markets. In the Netherlands or Aruba, where Sinterklaas’s arrival by steamboat is a major televised event, a bishop‑robed Sinterklaas with his book of children’s behavior can be more timely than Santa in mid‑November. In Poland or Hungary, boots on thresholds filled with sweets reference Mikulás more than the Coca‑Cola Santa.

Localize Visual Features, Not Just Language

Translating copy into Spanish or Finnish without changing the art is the easiest path, but it leaves value on the table. The research shows clear, recognizable visual cues for each tradition: Sinterklaas’s mitre and staff, Père Noël’s hooded cloak, Ded Moroz’s long coat and staff, Christkind’s crown and wings, Joulupukki’s rustic red clothing and connection to Lapland landscapes.

In practice, this means adjusting three things. The first is clothing and accessories. Lean on local renderings: a blue coat and fur hat for Ded Moroz, a green cloak and holly wreath for traditional Father Christmas, a silk shirt for Papai Noel, simple work clothes and a red cap for tomte. The second is props: shoes instead of stockings, camels or horses instead of reindeer, straw Yule goats, New Year trees, or Epiphany stars. The third is setting: a New Year party for Ded Moroz, an Epiphany parade for the Kings, graveside candlelight for Finnish Christmas Eve visits, or Caribbean harbor scenes for Aruban Sinterklaas.

These adjustments make designs feel researched rather than copied, and they communicate respect for the customer’s lived tradition.

Offer Parallel Lines Where Multiple Traditions Coexist

Several countries maintain parallel gift‑bring traditions. Germany and Austria have both Christkind and Weihnachtsmann. Spain combines Papá Noel and Los Reyes Magos. Italy features Babbo Natale and Befana. Finland presents Joulupukki as a Santa‑like figure but also connects to broader Nordic nisse and goat lore.

From a product strategy perspective, this is not a problem to solve but a portfolio opportunity. You can design a Christkind‑centric line with soft, religious or angelic aesthetics for customers who prefer that emphasis, alongside a more playful Santa line for those drawn to the global icon. In Spain or Latin America, you can stage Christmas Eve campaigns around Papá Noel products and New Year campaigns around the Three Kings. In Italy, you might position Befana designs for Epiphany gifts and stocking stuffers, while using Santa art for earlier December promotions.

The trade‑off is complexity. Each line requires research, design time, and perhaps separate ad creatives. But when your print‑on‑demand infrastructure is already set up for small, targeted collections, this kind of micro‑segmentation is exactly where you can out‑execute larger, less flexible brands.

Handle Sensitive Motifs With Deliberate Care

Not all traditional elements should be reproduced uncritically. The blackface version of Zwarte Piet is an obvious example; Aruban authorities explicitly discourage it, and Dutch society is actively renegotiating the character. A brand that doubles down on “classic” blackface imagery to look authentic is likely to attract backlash, not nostalgia.

Soviet‑styled Ded Moroz iconography can also be sensitive in contexts where Soviet history is remembered as traumatic, such as Ukraine or the Baltic states. In those markets, Saint Nicholas or other local figures may be the safer and more resonant focus.

Even without direct political controversy, some motifs skew very dark: Krampus whipping or abducting children, Grýla’s cannibalism, or the man‑eating Yule Cat are striking but intense. For adult or horror‑themed collections, they can be powerful visual anchors; for children’s apparel, they may not fit your brand promise.

The practical rule is to treat Santa imagery like any other culturally charged symbol. Validate it with local voices where possible, and when in doubt, soften, contextualize, or leave out the parts that punch down rather than delight.

Use Alternative Figures To Expand, Not Replace

A common entrepreneurial impulse is to “disrupt” Santa by rebranding him as something completely different. The research record suggests a more sustainable approach: treat alternative figures as additions to the ecosystem rather than replacements.

Nordic tomte, Japanese Hoteiosho, Italian Befana, Iranian Amu Nowruz, and Basque Olentzero each carry centuries of local meaning. Their power for your brand lies in that continuity. Rather than turning them into generic “quirky Santas,” design them recognizably and let your storytelling explain their differences. Customers often enjoy learning that certain characters are older than the American Santa or tied to their grandparents’ childhood customs.

This aligns with advice from anthropologists who encourage families to talk with children about Santa as a flexible cultural narrative, not a single literal truth. In brand terms, embracing multiple coexisting figures lets you serve both globalized and heritage‑seeking segments in the same market.

A Cultural Customization Matrix For Santa Imagery

The table below summarizes a subset of Santa‑type figures discussed in the research, with a focus on design‑relevant features. It does not cover every variation but illustrates how many moving parts you can customize.

Region / Name | Key visual cues and themes | Main gift date or period | Design focus for print‑on‑demand |

|---|---|---|---|

USA & Canada – Santa Claus | Red suit with white fur, round belly, white beard, elves, reindeer, North Pole workshop | Night of December 24 | Global default; works widely but risks feeling generic alone |

Netherlands / Aruba – Sinterklaas | Tall bishop in red robe and mitre, white horse, big book of children’s deeds, helpers under revision | Evening of December 5 and December 6 | Emphasize bishop imagery and harbor arrival, avoid blackface |

Germany / Austria – Christkind and Weihnachtsmann | Angelic child with crown and wings alongside red‑suited “Christmas man” | December 24 and sometimes December 6 | Offer soft, sacred Christkind art and more playful Santa art |

Spain & Latin world – Los Reyes Magos and Papá Noel | Three crowned kings with camels and star, plus red‑suited Santa | December 24 and January 5–6 | Stage separate Santa and Three Kings collections and campaigns |

Italy – Befana (and Babbo Natale) | Elderly woman on broom, shawl and skirt, sack of sweets or coal | Night of January 5 | Story‑driven witch imagery for Epiphany; Santa for Christmas |

Russia / Eastern Europe – Ded Moroz & Snegurochka | Tall figure in long blue or red coat with fur hat and staff, granddaughter in winter dress | New Year’s Eve | New Year aesthetic, avoid Soviet propaganda references |

Finland – Joulupukki | Bearded man linked to “Christmas goat,” red clothing, Lapland landscapes, ground‑bound reindeer | December 24 | Highlight Lapland, rustic feel, and goat symbolism |

Iceland – Yule Lads | Thirteen named characters with quirky traits, rustic clothing, sometimes with Yule Cat or Grýla | Thirteen nights before Christmas | Build character sets and story series rather than single image |

France – Père Noël | Bearded man in long red cloak with hood, sometimes with Père Fouettard | December 24 | Cloaks and shoes; decide whether to include the punishing partner |

UK – Father Christmas | Older man in green cloak with holly wreath and staff, gradually merged with red‑suit Santa | December 24 | Heritage green‑cloak line alongside modern red‑suit designs |

Brazil – Papai Noel | Lighter silk red‑and‑white outfit, electric‑light trees, summer atmosphere | December 25 | Bright lights, warm colors, and lighter fabrics in art |

Japan – Hoteiosho | Plump monk with big sack, sometimes eyes on back of head, New Year focus | New Year period | Blend Buddhist aesthetic with gift‑giver symbolism |

Iran – Amu Nowruz | Silver‑haired old man in traditional clothing with companion Haji Firuz | Nowruz (spring New Year) | Spring colors and Nowruz motifs rather than snow and reindeer |

When you design around this kind of matrix instead of assuming one global Santa, your catalog becomes a map of stories rather than a pile of interchangeable graphics.

Balancing Consistency And Localization In Your Brand

The last strategic question is how far to go. Hyper‑localized Santa imagery for every market can overwhelm a small team; a single global Santa may feel too flat.

One pragmatic approach is to treat the Coca‑Cola‑style Santa as your “global base layer” and then layer local variants where they matter most. Research on Santa’s evolution shows that the red‑suited figure is now widely recognized, even in countries where he is not the primary gift‑giver. That recognition has value for impulse purchases, tourist markets, and cross‑border buyers.

At the same time, the historical and anthropological sources make it clear that local gift‑bringers still carry real emotional weight. In markets like Spain, Italy, parts of Central Europe, Scandinavia, and Eastern Europe, investing in at least one strong local figure alongside Santa gives you depth. It also positions your brand as attentive rather than merely exporting American holiday imagery.

Operationally, that means starting with a prioritization exercise rather than an exhaustive rewrite. Focus first on countries where your traffic or orders are already meaningful and where the gap between global Santa and local tradition is widest. Use the research‑backed axes—date, clothing, transport, companions, and moral tone—to brief your designers. Over time, you can expand into more nuanced figures such as Basque Olentzero or regional German companions when your market justifies it.

FAQ: Santa Imagery For Global E‑Commerce

Do I really need different Santa designs for different markets?

You do not need entirely separate catalogs, but the research strongly suggests that some markets respond better when you acknowledge their specific figures and dates. A basic Santa line can work almost everywhere as a general winter icon, yet in countries with strong Saint Nicholas, Christkind, Three Kings, or Befana traditions, a localized design or two can significantly increase relevance and share‑worthiness. Think of these as targeted “accent collections” layered onto a global base, not as a reinvention of your entire product lineup.

Is it safe to use darker figures like Krampus or the Yule Lads?

These characters are firmly rooted in Central and Northern European folklore and are enjoying renewed interest, especially among adults who enjoy alternative or gothic holiday themes. The historical material shows that Krampus and some Yule Lad stories are genuinely frightening for children, involving kidnapping and cannibalism in the case of Grýla. That makes them better suited to adult apparel, posters, or party décor than to toddler pajamas. When you use them, lean into stylization and humor rather than realism, and avoid suggesting that they are harmless if your illustrations clearly depict fear or violence.

How can I keep Santa “on brand” if I customize him so much?

The deeper you go into the research, the more you see recurring core themes: generosity, midwinter celebration, and a moral narrative around caring for others. Saint Nicholas, Sinterklaas, Father Christmas, Christkind, Ded Moroz, the Three Kings, Befana, Joulupukki, the Yule Lads, Hoteiosho, and Amu Nowruz all share these threads. As a brand, you can anchor your visual diversity in that consistent message. Whether your character wears a mitre, a green cloak, a silk shirt, or a red suit, your product copy and storytelling can keep highlighting kindness, community, and shared joy rather than just consumption.

In the end, Santa is less a single character than a global design space shaped by centuries of stories, religious reforms, political projects, and local weather. The research record—from holiday historians and folklorists to anthropologists and museum curators—makes one thing clear: cultures keep reshaping their gift‑bringers to fit their values. As a print‑on‑demand entrepreneur, that is not a problem; it is your roadmap. When you respect those variations in your imagery, you do more than avoid missteps—you create holiday products that feel like they genuinely belong in the lives and traditions of the people you serve.

References

- https://exac.hms.harvard.edu/put-santa-in-photo

- https://covidstatus.dps.illinois.edu/classic-santa

- https://www.canisius.edu/news/santa-claus-image-tradition

- https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/a-pictorial-history-of-santa-claus/

- https://shgreenwichkingstreetchronicle.org/145141/features/dashing-through-different-cultural-perspectives-on-santa-claus/

- https://www.anchoragemuseum.org/about-us/stories-and-voices/chatter-marks-journal-podcast/articles/santa-claus-a-northern-icon/

- https://www.businessinsider.com/santa-claus-around-the-world-2017-12

- https://www.bbc.com/news/newsbeat-38414996

- https://www.history.com/articles/santa-claus

- https://www.kyivpost.com/post/44051